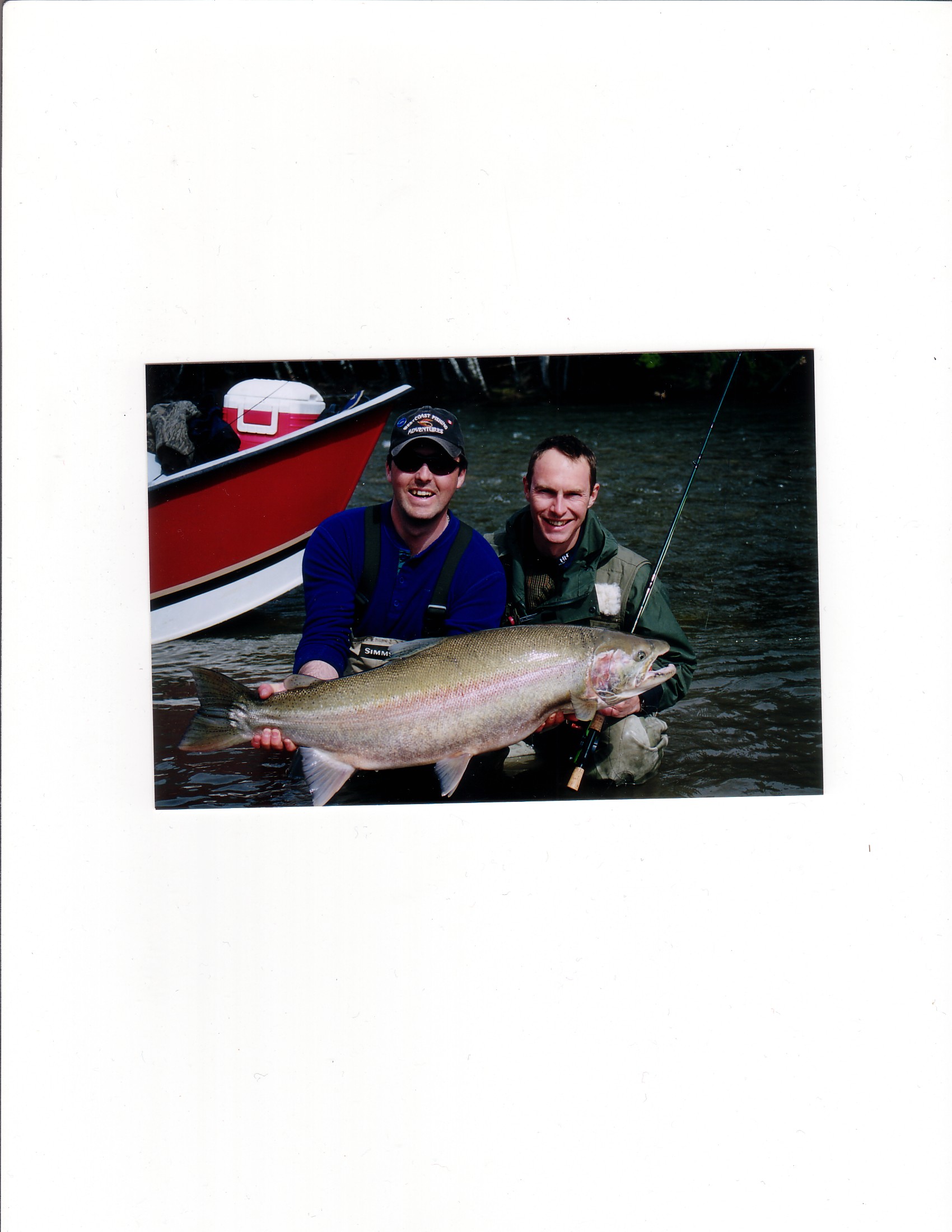

A Fish Tale to remember.

When Andrew Fairclouth hooked, played and released the first steelhead of his life, a nice 12 pounder, there’s no way he could have known that a dozen casts later he’d make fly fishing history. But that’s exactly what happened on a spring day just a few seasons ago in northwestern British Columbia.

“He thought that fish was the best thing since sliced cheese,” says Fairclouth’s guide that day, Gill McKean, who owns West Coast Fishing Adventures in Terrace, B.C. “Andrew had come all the way out here from the U.K. to hook a steelhead on the fly and he was really happy about it.”

After the fish swam off, McKean tied on a new tippet for Fairclouth and replaced the fly, a “Gill’s Creamsicle,” which is basically a pimped out orange bunny leech of his won design. Fairclouth then waded back out to the same spot and resumed casting. “He pretty much was still in the same spot where he’d caught the fish, though I was trying to get him to cast a little further out,” says McKean.

When Fairclouth finally hit the sweet spot on the distant seam, another steelhead ate the fly. This one was different than the first…much different.

“It was a super aggressive fish and it hit that fly just as it touched the water,” says McKean. “It wasn’t messing around. The water in that spot’s about 5 feet deep and that steelhead came straight up and attacked it.”

When it felt the sting of the hook, the fish boiled and McKean got his first glimpse of the leviathan.

“It looked like a washing machine out there, eh!” he says. “At first, I figured it had to be a big early spring Chinook. Though it doesn’t happen all the time, we have caught a few big kings in late April while fishing for steelhead. Then I saw some red on him and knew it was a steelhead. At that point, the thing just went totally berserk and ran like hell out of the pool and downstream.”

The fish was so hot that all Fairclouth could do was hang on. He leaned into the beast as much as he dared with his 8-weight Thomas & Thomas, but the steelhead continued to rocket downstream. Like a bad movie slowly unfolding right in front of him, McKean watched helplessly as the hooked locomotive streaked right for a big logjam at the bottom of the run. As a last ditch effort to avoid certain heartbreak, he raced down the bank and got ahead of the fish. McKean then waded out into the middle of the run in hopes of getting the fish to turn back upstream. Eventually, he succeeded and Fairclouth was able to work the giant steelie back into the pool.

The flight raged for close to 40 minutes — towards the end of which the reel wiggled loose of the reel seat. After that little situation was contained, Fairclouth was eventually able to lead the great fish to the shore.

“As we got it to the bank, we just stood there staring at the thing,” says McKean. We couldn’t believe what we were seeing. It was huge and so thick all the way from the head down through the tail. It’s girth never snaked out like a lot of fish do. And its adipose fin was like a rudder – it was massive and looked like one off a big spawning male Chinook. I had a tape in my pocket and we got some quick measurements – the fish was 41.5 inches by 25.5 inches. It was unbelievable, man – definitely the biggest steelhead I’ve ever touched.”

And that’s saying something, considering McKean lives and guides in a region that produces more monster salmon and steelhead than anywhere else on the planet. He’s caught and guided people to countless 20 plus pound steelhead, including a line class 28 pounder taken on spinning gear and a fish or two in the 30-pound range.

“Up here, we come across 20 pounders fairly regularly, depending on the year and individual season,” he says. “Moby was in an entirely different class all together.”

While Moby was never weighed prior to release, he was very likely in the mid 30’s. Using Sturdy’s Weight Formula (length x girth squared x .00133), which was developed for Dean River steelhead, you get an amazing 35.8 pounds. The Skeena/Kispiox Formula (length x girth squared divided by 775) designed to estimate the weight of the extra girthy fish those drainages are prone to produce, gives you 34.8 pounds.

In either case, Fairclouth’s steelhead would eclipse the fish long accepted as the world fly rod record of 33 pounds, set by Karl Mauser in 1963. Just for kicks, I called the International Game Fish Association, which keeps all-tackle, fly and line class records for dozens of fresh and salt water species to see what the official fly rod record for steelhead currently is. Interesting enough, Mauser’s fish was never recognized by the IGFA, according to Becky Wright, IGFA’s World Record Coordinator. The organization doesn’t have a category for steelhead and instead puts all rainbows – anadramous and otherwise – into the same group. Right now, the all-tackle mark for the species is that freaky 43-pound, 10-ounce triploid mutant from Lake Diefenbaker taken last year. In the fly department, the largest fish is a 30-pound, 15-ounce rainbow from Germany’s Ruhr River – obviously not a steelhead, either.

So, had McKean and Fairclouth gotten Moby’s official weight, he’d likely be in the record books as the largest recognized steelhead taken on a fly in the world. Of course, with the take of wild steelhead banned in B.C. (we here in the states should follow suit!), getting weights of big fish without causing them too much unnecessary stress is a bit problematic. To that end, fish even larger than Moby have been caught and released in recent years. The largest I’ve found while searching the internet was a 46.5 x 26.8 incher hooked in the Skeena by an Italian angler that may have been as large a 44 pounds! Still, Fairclouth is among very select company having landed a steelhead in the mid 30-pound range…on a fly (and don’t even get me started on the fact that it was only his second-ever career steelie).

Now, the story of Mody doesn’t end there. While catching a fish like that gets very close to “miracle” status in its own, it’s also a wonder that there’s even any photographic evidence of the event considering what happened after McKean put the measuring tape to the fish.

“Andrew insisted on holding Moby up for a photo,” he says. “But he couldn’t hold on and dropped the fish back into the water. The hook was still in his mouth but the line got all twisted around the rod and reel – it was a total cluster!”

As Moby regained his wits, he started heading back towards deeper water. That’s when McKean made a heroic dive and got a grip – just before the line came tight against the tangles.

“I held him up really quick,” says McKean. “And then we whipped off three pictures – which turned out to be the last three shots on my roll of film…”